Icy Hell

“No one had ever made a trip directly through the Endicotts..."

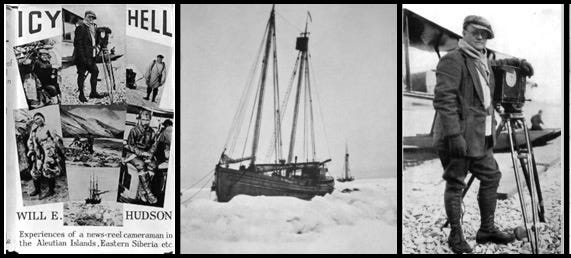

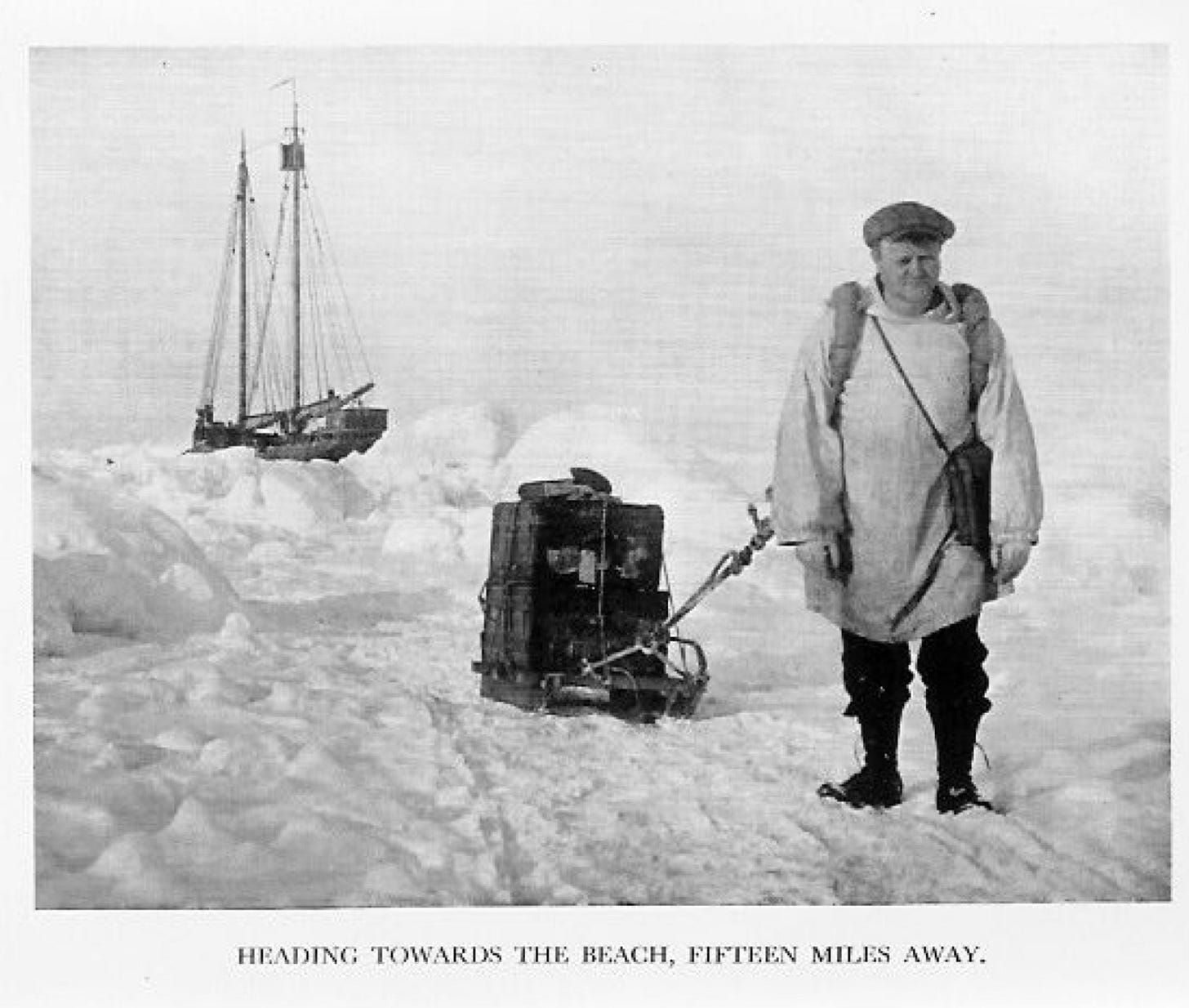

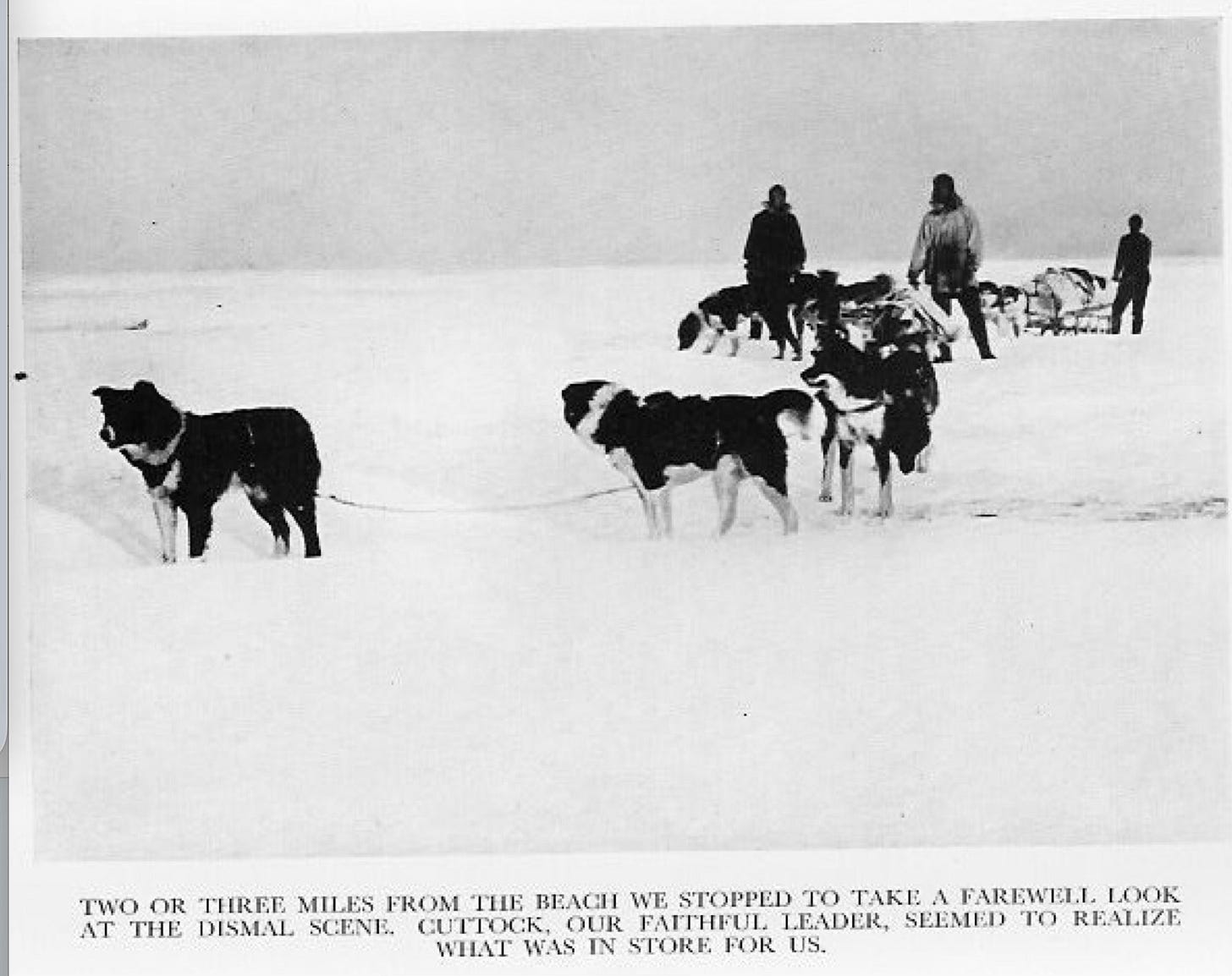

The current issue of Alaskan History Magazine, Vol. 4, No. 6, features an excerpt from Will Hudson’s rare and hard-to-find 1937 book ‘Icy Hell,’ detailing the harrowing overland journey he and three others made across the great Brooks Range to the village of Fort Yukon when their ship ‘Polar Bear’ became trapped in the polar ice pack in 1913. The photographs above and below are from Hudson’s book.

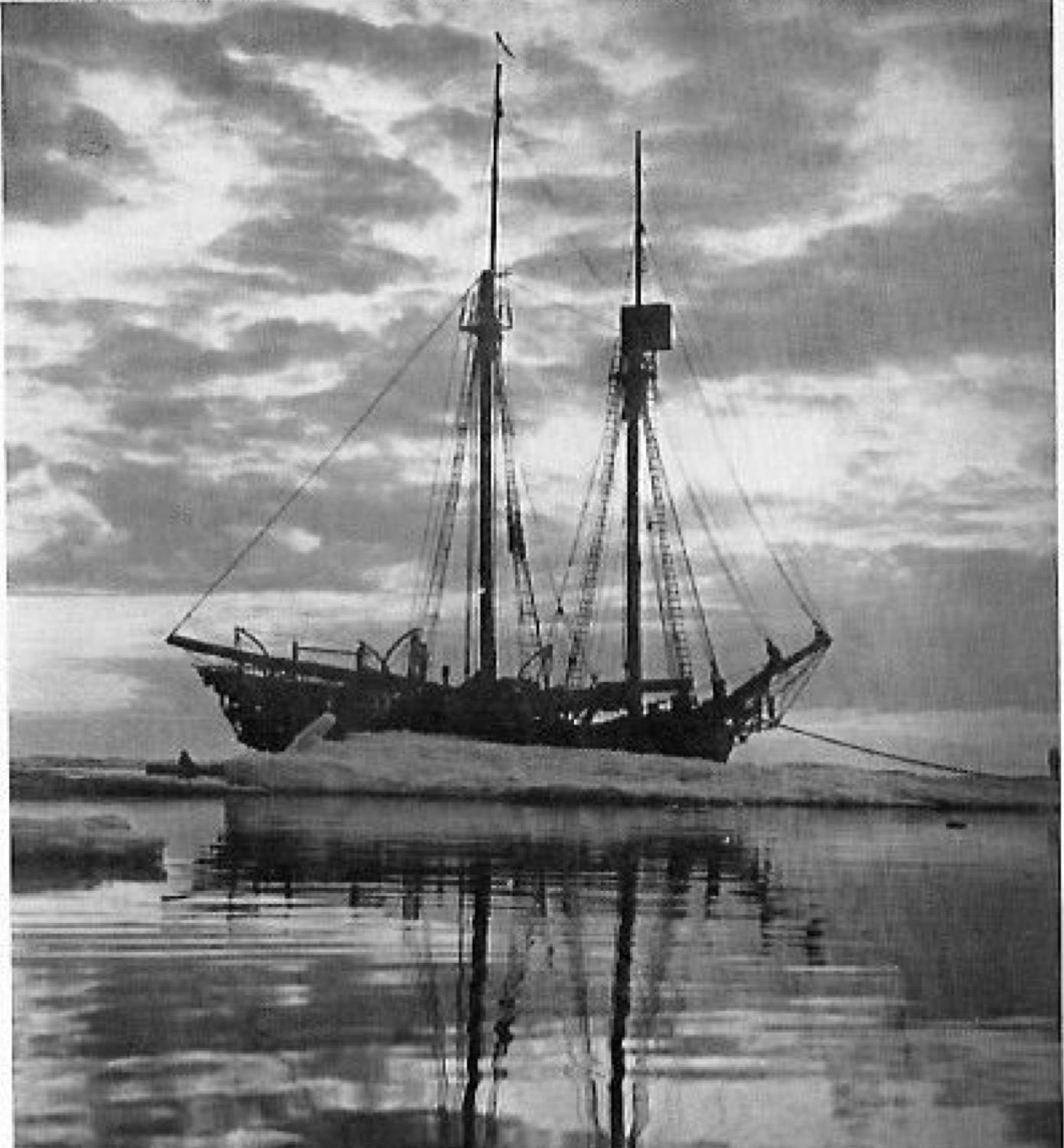

The Polar Bear, a 90’ 81-ton schooner built in 1911 by E. W. Heath Co. of Seattle, had been chartered by a group of college graduates who wanted to go to Alaska to go hunting. The cost of the trip was sponsored by Harvard University, and possibly to justify the expense, the school sent two naturalists along to collect natural history specimens and provide a kind of scientific purpose to the trip. Will Hudson had been invited to come along as the official cinematographer, he had worked as the first still photographer on the staff of The Seattle Post-Intelligencer since 1908.

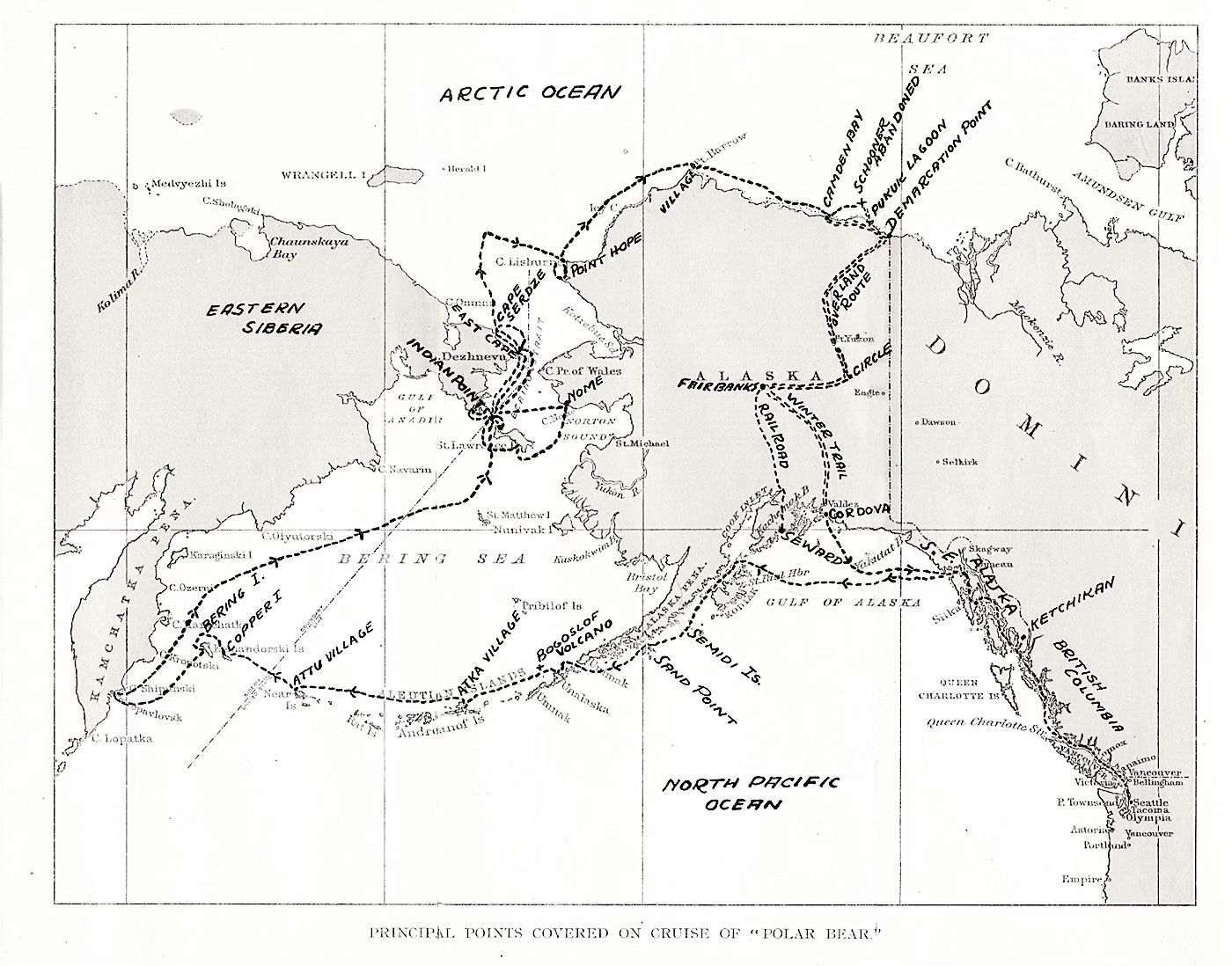

When the ship was caught by pack ice and forced to overwinter on the exposed coast of northern Alaska, the captain, Hudson, and two other men left the ice-bound ship to be cared for by its capable crew and traveled south with two dog teams, crossing the uncharted Brooks Range, stopping in Fort Yukon, and mushing up the Yukon River to Circle. From there they rode on horse-drawn sledges to Fairbanks, then continued south to Cordova and home to Seattle in time for Christmas. Captain Louis Lane returned to the north the following spring and met the Polar Bear at Herschell Island; the tough little schooner had come through the winter safely under the skilled handling of her crew.

At the end of his foreword to ‘Icy Hell’ Hudson notes: “In no way do I make any claim as a writer. This narrative is simply a cameraman‘s experiences while traveling over an unbeaten path. I had never visited this country before and never expected to visit it again, so I kept my eyes and ears open, made many copious notes, and took many pictures.”

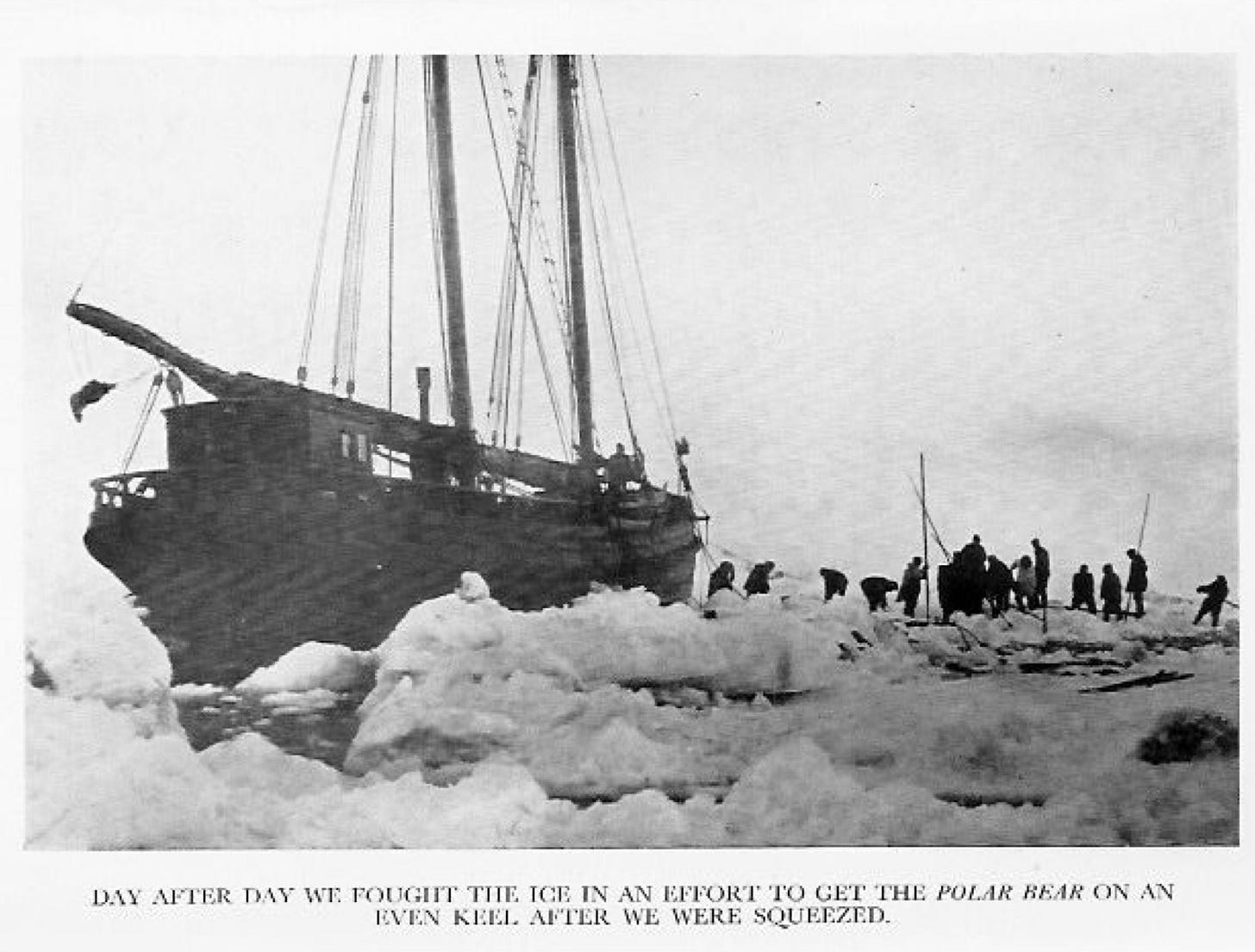

The Polar Bear departed Seattle on the morning of April 13, 1913, headed north to Alaska. After stops at various ports of call along the Alaskan and Russian coasts, Captain Louis Lane charted a course to the Arctic Ocean, arriving at Barrow, at that time the largest Eskimo village in North America, toward the end of July. On July 25th the Polar Bear headed for Herschell Island, 400 miles to the east, under fair weather and with the crew in good spirits. After many adventures along the northern shore of Alaska, by September the Polar Bear was icebound near Humphrey Point, east of Kaktovik, on the Beaufort Sea.

Concerned that the ice might crush and sink the ship, the crew departed the schooner and set up a camp on the beach, securing their supplies. With that done, Hudson explained why some of the members were going to leave the camp and hike overland, while the others waited out the winter with the ship: “I had pictures that I must sell in order to make a living. The skipper had urgent business affairs on the outside that needed his personal attention. The two members of the party that were considering going out had no business cares to force them to go anywhere. Just why they were so anxious to make the trip has always been a mystery to me.”

Will Hudson, Captain Louis Lane, and college boys Eben Draper and Dunbar Lockwood were the four who would leave Humphrey Point for the 260-mile overland trek. Hudson noted: “No one had ever made a trip directly through the Endicotts by the course we were contemplating. We had been told by some natives earlier in the season that it could be made from where we had located our camp.”

The group decided to take ten dogs which they had obtained from local natives and a trader, and a nine-foot long sled made of oak, spruce and hickory, with runners four inches wide and shod with heavy brass, and a toboggan of the same length with steel-shod runners. A camp stove, grub box, tent, a lantern with two extra glass globes, three watches, two rifles, two single-bit axes, two flat files, a small emery stone, and a small repair kit.

They stopped to spend the first night with an Eskimo family, and the second night at a trader’s home, then they turned south into the wild and rugged mountains. Their journey is detailed in 14 pages of photos and excerpts from Hudson’s book in the current issue of Alaskan History Magazine.

Also in this 64-page issue: The friendship between Charles Sheldon and Harry Karstens and the roles they played in the beginnings of Denali National Park, the history of Rika’s Landing Roadhouse on the Richardson Trail, the travels of Lt. Frederick Schwatka in 1883, the history of barns in Alaska, and the history of Juneau told via excerpts from a 1920 article. The issue is $12.00 postage paid. All back issues—dating back to 2019—are available, and indexes to the 20 issues now in print make it easy to find a specific subject of interest. Click below for details: